Munich exhibition documents German army atrocity in Afghanistan

By Wolfgang Weber

8 February 2011

On the night of September 4, 2009, the order by German army Colonel Georg Klein to bomb a gathering of villagers, including many children and young people, in the province of Kunduz, Afghanistan resulted in exactly 91 deaths, as well as a number of serious injuries.

These were the facts exposed by two journalists, Stern magazine editor Christoph Reuter and photographer Marcel Mettelsiefen, after several weeks of research. The results of their work are now being presented from February 2 to 20—paralleling the NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) security conference—at Munich’s House of Literature in the exhibition “Kunduz—September 4, 2009: Looking for clues” and published in book form under the same title by Rogner & Bernhard. The exhibition is a harrowing documentation of the greatest war crime committed by German officers since the fall of Hitler’s Third Reich in 1945.

Location of the German army massacre in Kunduz (© Marcel Mettelsiefen/oh)

Location of the German army massacre in Kunduz (© Marcel Mettelsiefen/oh)Invited to speak at the exhibition’s opening ceremony on February 1, the two writers were accompanied by a third speaker, Prof. Roger Willemsen, a commentator known from many TV talk shows for his sharp criticism of the war in Afghanistan.

At the beginning of the event, Christoph Reuter briefly sketched the circumstances prior to the massacre, pointing out that Colonel Klein—contrary to military regulations—ordered the bombing solely based on allegations made by a single informant. Klein argued that he had believed the crowd gathered around the two trucks consisted exclusively of Taliban fighters; on this basis all proceedings against him were suspended. Neither Klein nor any other section of the army bothered to find out exactly who and how many they had actually killed. The NATO commission of inquiry and even the Red Cross spent only a few hours at the location, without trying to determine the exact number of victims or identify them. The official NATO report cynically noted that there were “between 17 and 142 casualties”.

Opening meeting with the photographer Marcel Mettelsiefen and journalist Christoph Reuter

Opening meeting with the photographer Marcel Mettelsiefen and journalist Christoph Reuter The exhibition in Munich

The exhibition in MunichHowever, following the forced resignation of the Defence Minister Franz Josef Jung (Christian Democratic Union, CDU), neither politicians nor the media took any further interest in the victims. They concerned themselves only with Jung’s successor in office, Karl Theodor Maria Georg Achaz Eberhardt Joseph, Baron of zu Guttenberg. The Defence Ministry under this dashing scion of the nobility had absolutely no interest in pursuing the matter, preferring to close the case rather than face the liability of compensation payments for the bereaved. Only when it was confronted with Reuter and Mettelsiefen’s precise list of the 91 dead, did it finally condescend to dole out something for each victim—even though this amounted to no more than a derisory €5,000.

Owing to the two journalists’ empathy and tact, as well as their perseverance and patience, they were able to gain the trust of the long-suffering villagers and talk with groups of 10 to 15 in hour-long sessions for several weeks. Only a few photographs of the dead had been taken, but the journalists were given these by the victims’ relatives. The family members could see that they were not going to use them as sensational images to excite public interest, but that the journalists were genuinely concerned about the Afghan people, their dead and their suffering. Christoph Reuter painstakingly identified the dead and their surviving relatives, their family relationships, their often tragic loss of several sons, brothers or other relatives.

Marcel Mettelsiefen photographed the relatives after each of the group talks. His photos were not the lurid kind usually found in the tabloid press. They are quiet and reserved, but therefore all the more moving and thought-provoking; portraits of old men who grieve for their sons and grandsons, of boys who had identified their fathers among the dead after the massacre, often finding only body parts or pieces of clothing.

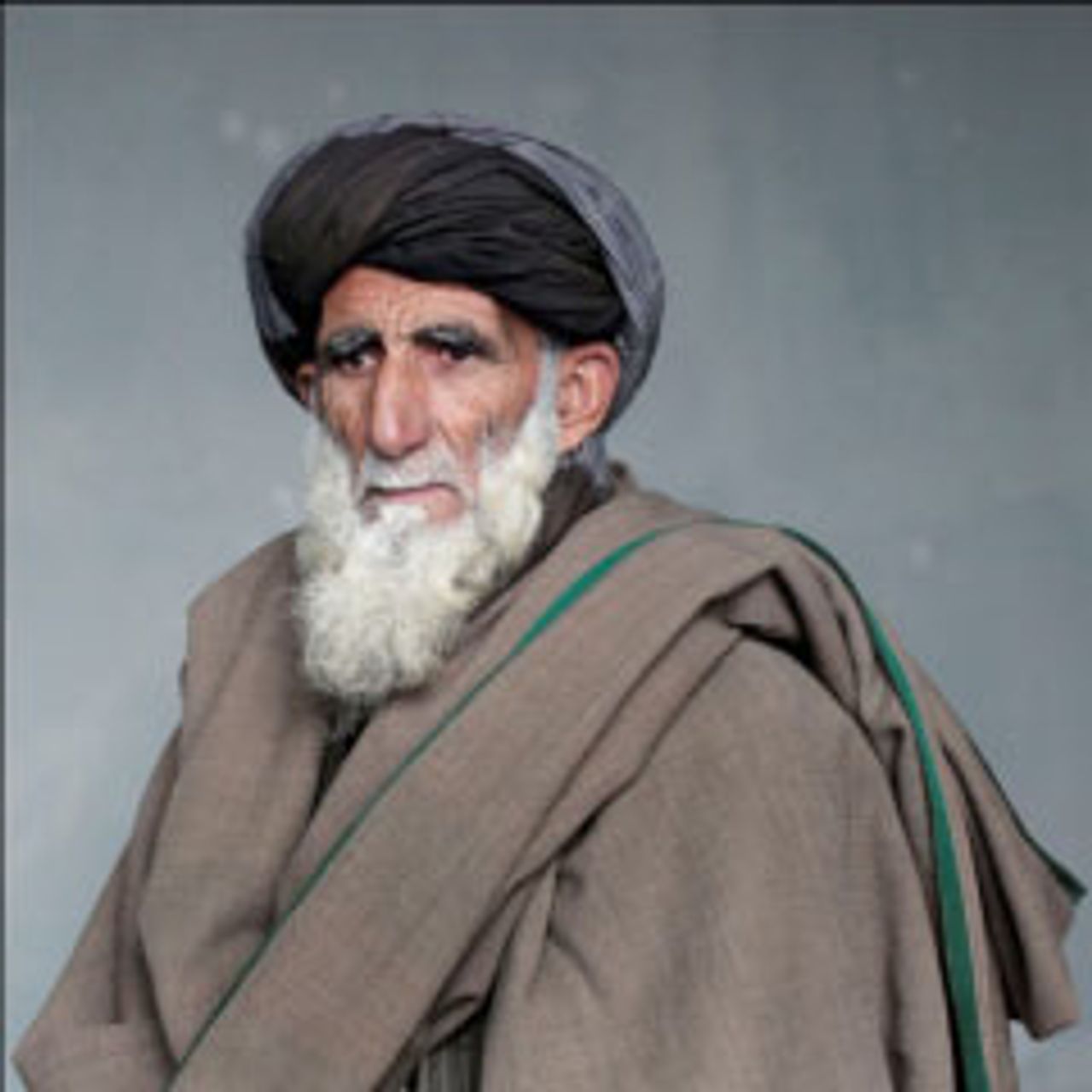

Mir Akbar (© Marcel Mettelsiefen/oh)

Mir Akbar (© Marcel Mettelsiefen/oh)Mir Akbar, for example, lost his 21-year-old son that night. When the attack occurred, he heard the explosion and immediately started running. But on reaching the site of the bombing, he found only one of his son’s legs and his hair. The rest of the corpse could not be found.

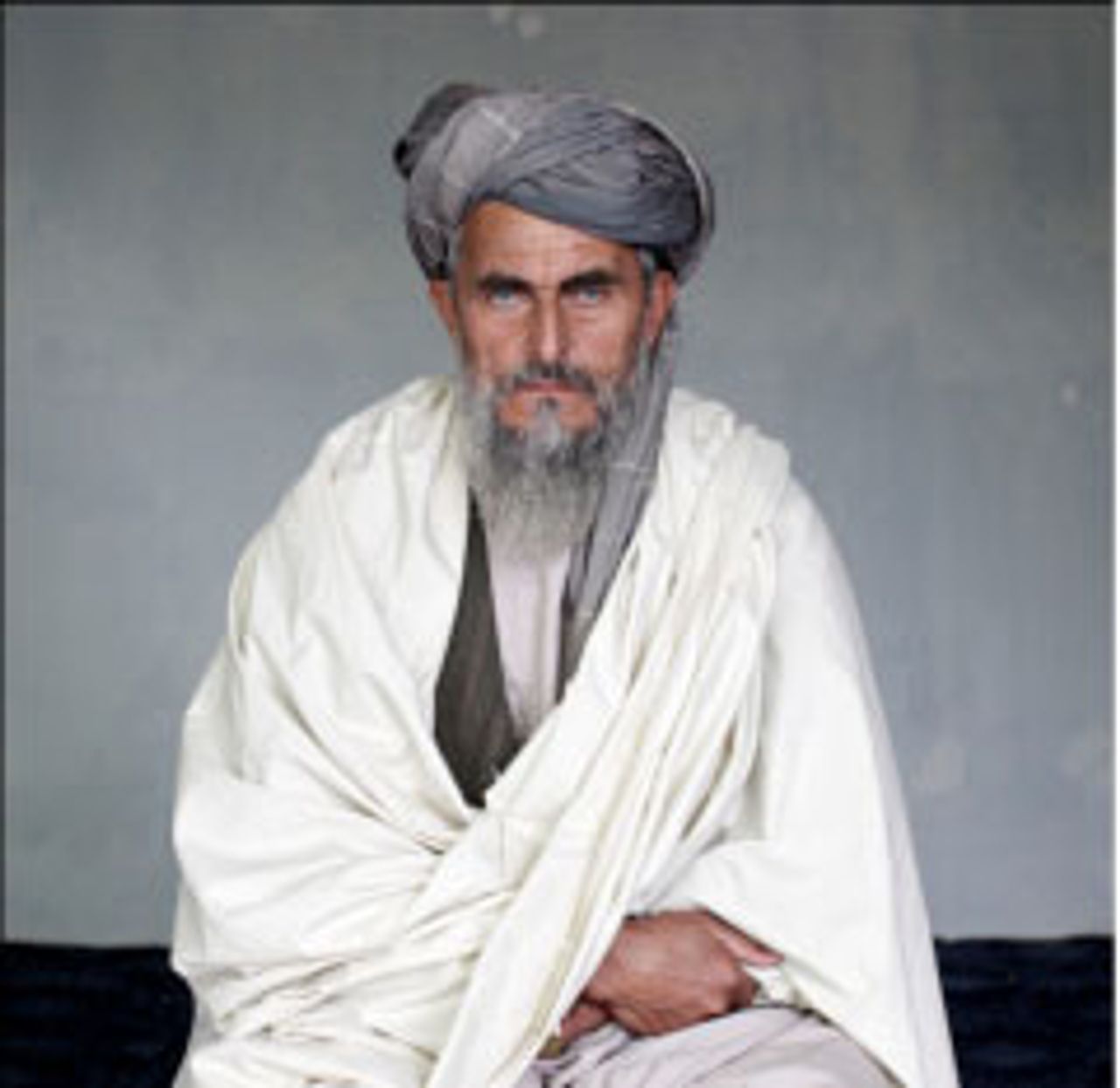

Nazir Mir (© Marcel Mettelsiefen/oh)

Nazir Mir (© Marcel Mettelsiefen/oh)Nazir Mir is shown mourning his father, Mohammed Akram, who ran out at one o’clock that night, after hearing that much needed gasoline could be tapped from the trucks. It was not until the next morning that Nazir Mir arrived at the scene of the disaster, finding only the remains of his dead father.

Abdul Daiane (© Marcel Mettelsiefen/oh)

Abdul Daiane (© Marcel Mettelsiefen/oh)Directly after the armed forces’ attack, Christoph Reuter and Marcel Mettelsiefen visited Kabul hospital, where they came across a young boy who had been found among the few survivors by relatives and had been immediately driven to the hospital. A few hours after he had indicated to them that he was the son of Abdul Daiane and allowed himself to be photographed, he died of his burns. Through their talks with the villagers, the two journalists were able to find Abdul Daiane, who tearfully thanked them for the photo of his son. Apart from this son, he had also lost another. Another small boy, 13 years old, had lost all his male family members and thus had to leave school to assume the role of family head of household.

Following the speeches of the two journalists, Roger Willemsen addressed those present at the opening ceremony, eloquently and vividly describing Afghanistan in a kind of personal travelogue as a country torn apart by contradictions and suffering, steeped in rural poverty and urban corruption, terrorised by tribal feuds, warlords, drug barons and puppets of foreign powers. According to Willemsen, Afghan society was a relatively peaceful and socially balanced land in the 1960s and 1970s. A unique melting pot resulting from two millennia of the ancient Greek Hellenistic and Indian Buddhist cultures, it was at that time undoubtedly a country of high cultural development. However, after 30 years of war and particularly after the widescale bombing of recent years, that culture has now been completely destroyed in material terms. On the other hand, the spiritual values, the ideas and social concepts, the way of thinking, the hospitality and musicality—everything that constitutes spiritual culture could not be destroyed by the bombs and are still to be found there.

Willemsen also talked about his experience and that of his girlfriend Nadia Nashir-Karim as patron and chairperson, respectively, of the Afghan Women’s Association. The daily endeavours of this association—for example, supplying 30,000 people with drinking water, constructing and maintaining schools for more than 2,000 women and girls, securing medical care for about 20,000 people—all of this, as well as the work of other humanitarian relief agencies, is by no means facilitated by the bombings, field combat or sheer military presence of NATO forces, but only impeded and often completely destroyed. Concluding his speech, Willemsen observed: “This war cannot be managed with the means that have been adopted; this war has no argument to justify it, no rationale to legitimise it!”

The ensuing discussion gave rise to a number of quite controversial views. Visitors often expressed their esteem, their regard for both the courageous and highly professional work of the two journalists, and the effective humanitarian aid being organised by Willemsen.

However, the speakers’ thoughts on the rather limited political prospects for Afghanistan’s future and an end to the war met with considerable protest. For several years, Willemsen has energetically advocated an immediate withdrawal of the army from Afghanistan, although he has recently come to accept the German government’s proposal of 2014 as the latest date for disengagement. In order to use the time until then in a meaningful way, he recommends the provision of training programmes for the police, the judiciary and other national institutions. Speaking earlier in the ceremony, he had very clearly and emphatically pointed out that these national institutions—for example, the parliament—were an Augean stable of corruption, dominated by all the forces that had terrorised and bullied the country for years: drug barons, local warlords, and President Hamid Karzai, the pure personification of corruption, at the head.

Christof Reuter said the choice between extending the stay of NATO troops and withdrawing them immediately was, as the German saying goes, the same as one between plague and cholera. He feared that, following the withdrawal of armed forces, there might be a “Night of Long Knives” (alluding to Hitler’s liquidation of the officers of his own standing army in 1934), an unrestrained outbreak of the clan and tribal feuds so far suppressed, and the country could sink into real chaos. All three admitted that Afghanistan’s present misfortune had begun with the arrival of foreign troops and the US was responsible for promoting and training the Taliban, who they now claim have to be fought. However, they expressed only cluelessness and pessimism when it came to suggesting a way out of the disaster brought about by the West.

Nevertheless, the journalists’ efforts and the documentation they produced have made a valuable contribution to the struggle to end the war. This is so because a prospect for peace will only emerge when the populations of the belligerent countries—such as Germany, France, Australia and the US—open their eyes to the war crimes in Afghanistan and intensify opposition to their respective governments.

No one should miss the opportunity of attending Chris Reuter and Marcel Mettelsiefen’s exhibition about the German army’s massacre in Kunduz and the fate of its victims. We also recommend their book to all who are concerned about the war, argue for its end, and call for an immediate withdrawal of the German and other invading armed forces.

No comments:

Post a Comment